“A recent article in a New York newspaper reported that there were large colonies of people living under the city. The paper was incorrect. What is living under the city is not human. C.H.U.D. is under the city."

Great tagline…great movie!

Great tagline…great movie!

C.H.U.D. (Douglas Cheek, 1984) is a classic of the 1980s. It’s gooey and gory and goofy. But beyond that, like any horror movie worth its salt, it’s got some interesting things to say about what life during the Reagan years was doing to the people who lived then…above and below the streets of our larger cities.

C.H.U.D.: come for the slime, stay for the subtext!

Let’s take a closer look...

It’s 1984. It’s America. Ronnie Raygun has been guest-starring as

“The President of the United States” for the past four years. And Noo Yawk, Noo

Yawk has yet to be Disneyfied. The buildings are still decrepit, the streets

are still mean, and the people are still decrepit and mean.

The American urban landscape has never seemed closer to the debauched environs

surrounding Castle Dracula.

As our film opens, a woman walks her dog down the rain-soaked

streets of the city…although seeing this is NYC in the 80s, they could easily

be blood-, urine-, or semen-soaked, as well. Not being the sharpest knife in

the drawer, our dog-walker stops her excursion next to a steaming manhole

cover. In an extreme example of New York City’s “Keep Our Streets Clean”

campaign, an animal-like arm shoots out from the manhole, grabs ahold of a

fashionably clad foot, and pulls the damsel and her doggie into the

netherworld.

Self-cleaning streets! Maybe Mayor Ed Koch wasn’t as big a

knucklehead as he seemed?

The next day we are introduced to photographer George Copper (John

Heard). George is a man caught between two worlds: the lucrative world of

fashion and commercial photography and the artistic world of documentary

photography. George’s lady friend, Lauren Daniels (Kim Greist), is

a model who is counting on him to work with her on her next shoot. George,

however, has plans of his own.

George had been working an exposé for a magazine highlighting the

lives of the scores of homeless people who live beneath the streets of the

city. The article’s deadline is fast approaching, and George’s editor, Derrick,

wants his pictures. George is an artiste and will serve no

wine until its time, as it were. He is holding back the photos he has in order

to find the perfect shot. Unfortunately, enough time has passed that George is

unaware of where his original subjects have gotten off to. As luck (or

convenient screenwriting) would have it, one of his photographic subjects soon

gets in touch with George…people are allowed one phone call when they are

arrested for trying to lift a cop’s gun, after all. Relieved to have an excuse

to leave, George hightails it from Lauren’s fashion shoot to bail the poor

woman out.

Meanwhile, the police are having quite a rash of “missing persons”

cases lately. Captain Bosch (Christopher Curry) has been

keeping a lid on these cases in the Lafayette neighborhood for Police Chief

O’Brien (Eddie Jones) long enough. Fed up with the

bureaucracy, Bosch takes things into his own hands.

He visits a local soup kitchen run by the “Reverend” A.J.

Shepherd (Daniel Stern). The Rev and Bosch have a history together

— and it ain’t necessarily the kind that breeds love and trust. The Rev has

reported that a lot of the homeless people that visit his shelter have gone

missing. And not just the “regular” street people, either. It is specifically

the “undergrounders” who have disappeared. Bosch discloses that other people

have gone missing, too, including his wife (the woman out walking her dog at

the beginning of the movie). Soon, the Rev and the Captain join forces with

George Cooper to investigate not only the missing homeless folks, but the

reasons for a so-called “routine” inspection of the sewers of NYC by the

Environmental Protection Agency and the Nuclear Regulatory Committee.

A movie like C.H.U.D. walks a dangerous

line. At any moment it could cross into the utterly absurd and become more

humorous and ridiculous than it needs be. Thankfully, the acting in this flick

is very good. Each of the leads is your typical New York school character

actor, and each delivers his/her lines with utter believability. The early

scenes with Bosch and the Rev are especially juicy, and they lend credences to

the history these characters have together, as well as the grudging respect

that grows between them.

But let’s face it: we ain’t watching C.H.U.D. for

the acting — no matter how good it may be. This is a monster movie, after all,

so bring on the latex, the fake blood, and the glowing goo! The Cannibalistic

Humanoid Underground Dwellers are kept in the background for most of

the film. Their presentation in the first half of the movie is made up of

off-screen growls and shadows. This reluctance to show the monster isn’t

like Steven Spielberg’s choice to hold back the shark’s

introduction in Jaws (1975) because the SFX didn’t

work. Au contraire! Holding back only makes their eventual appearance more

shocking. The CHUDs look creepy and great. A combination of full latex body

appliances with some animatronics and puppets thrown in for the really outré

stuff (stretchy neck CHUD, fer instance!), the monsters add a high degree of

grotesquery and believability to the proceedings. Like any good monster, you’ll

want to cover your eyes and look at the same time.

All of the above — the acting and the SFX — are used to good effect

to comment on a world in which government on every level is more concerned with

covering its ass over the disposal of nuclear waste in a major metropolitan

area than with the effects said waste has on the under- and un-privileged

homeless. Laugh all you want, but C.H.U.D. is an

excellent example of the ways that the genre films of the 1970s and 1980s were

better adapted than their more upscale brethren for dealing with the horrors of

modern life. Life during the time of the Vietnam War, Watergate, Love Canal,

Three Mile Island, the Moral Majority, and the rise of the New Right had to be

understood as being a complete fantasy — albeit the darkest and most

nightmarish of fantasies. Movies like John Carpenter’s The

Thing (1982), Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982),

and, yes, C.H.U.D. are horror films on one level and

political allegories / critiques on another. Understanding the monster in the

closet or under the bed is the only way of understanding the monster behind the

pulpit or in the Oval Office.

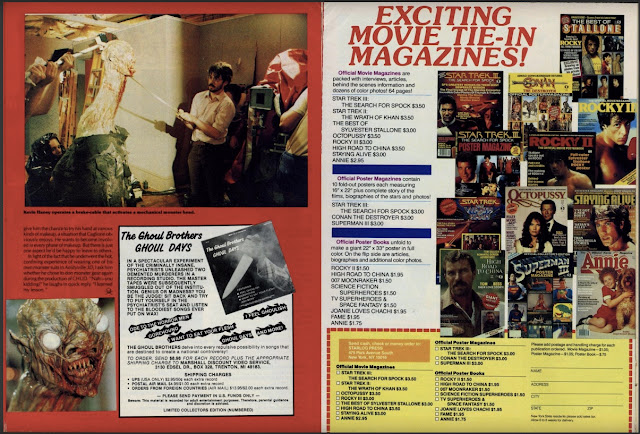

C.H.U.D. was one of those movies that I knew more from

pictures in Fangoria magazine than from actually seeing

it. Looking obsessively at the film stills and behind-the-scene photos of the

monsters in the movie creeped me the hell out as a little kid. The greenish

color in all of the photos gave a patina of sordidness to

the flick. Thanks to HBO (and parents who let me stay up all

hours watching whatever dreck I wanted), I saw the movie about a year after

reading about it. At the time, I was more than happy to enjoy it as a

straight-up gory monster movie. Time has been kinder to C.H.U.D. than

it has to other movies of the time period. Now when I watch it, I see it as the

end product of a society searching for a mythology that will help it deal with

horrors. Not of the silver screen variety, mind you, but of the all-too-real

kind they saw on the evening news.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think? Let me know!