You open your eyes. It is morning. Sunshine is streaming through the slats of your window blinds. The straight lines of light on the floor are slowly creeping their way up the edge of your bed. You pull yourself upright to sit on the edge of your mattress. Your hands rub the crust from your eyes while your feet find your slippers. You grab your phone before stumbling out to the kitchen. As you lean against the counter, listening to the coffeemaker burp and hiss, you check your favorite blog, LARPing Real Life. It’s another great “Long Form Friday” post. This time, it’s a novella by the Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes called Aura. It’s a shame, you think, that this poor slob can’t make a living from his writing. You decide to send the blogger twenty bucks. Twenty? More like fifty! A hundred! Anything to keep these great little essays coming your way...

Well...you can’t blame a starving artist for trying.

It may or may not be morning when you read this, but today’s Blog-o-ween 2023 post really is all about that great short little novel by Carlos Fuentes, Aura. Unlike the other stories we have covered this month, which have all been written in either the first-person, the third-person limited, or the third-person omniscient, Aura is written in the second-person present. It addresses the reader directly as “you” in this moment of “now.” This choice of narrative voice and the story that Fuentes tells conspire to place the reader in an interesting, if not frightening, time-space conundrum. How does this happen? Well...you scroll down the page...you read on...you can’t help but be fascinated...what is Carlos Fuentes’s Aura all about?

“You’re reading the advertisement: an offer like this isn’t made every day. You read and reread it. It seems to be addressed to you and nobody else. You don’t even notice when the ash from your cigarette falls into the cup of tea you ordered in this cheap, dirty café. You read it again. ‘Wanted, young historian, conscientious, neat. Perfect knowledge of colloquial French.’ Youth...knowledge of French, preferably after living in France for a while...‘Four thousand pesos a month, all meals, comfortable bedroom-study.’ All that’s missing is your name...”

Felipe Montero, young French-speaking historian, conscientious, neat, follows the advertisement’s direction to a neighborhood in the old center of the city. There, the buildings are a jumble of the old and new: the ground floors are all new shops and businesses selling cheap wares; above, the second floors are untouched by time. “Up there,” Felipe says (or you say), “everything is the same as it was.” Before entering the house at 815 Donceles Street, Felipe tries to “retain some single image of that indifferent outside world.” Then, the door closes behind him and he is enclosed in darkness.

In the house, he meets an old woman, Consuelo. She is the widow of General Llorente, whose journals Felipe is to organize, finish, and publish before her death. Also living in the house is the widow’s young niece, Aura, who doesn’t seem to say much, but for whom Felipe quickly develops strong feelings.

As the work on the General’s writings progresses, Felipe finds himself drawn deeper and deeper into the the story of Llorente and Consuelo’s life together. What is the connection between himself and the General? What is the connection between the old woman and her niece? Why is it when one talks, the other’s lips move? For what is Felipe being groomed?

Written in 1962, Aura is a magical realist novel that has more to do with reality than one suspects at first glance. The man whose letters Felipe is asked to organize was a member of the conservative group who welcomed and fought for the French invasion of Mexico in the 1860s. When that insurrection was defeated (thus giving us Cinco de Mayo), Llorente, who was forty-two at the time, and his young bride, Consuelo, went into exile. One hundred years later, this same conservatism is reawakening in Mexico. In order to succeed, it must infiltrate, absorb, and be reborn in the youth of the country. Aura, then, is about the return of the repressed.

The second-person present narrative works in Aura like a black magic spell being cast over the reader. Indeed, it is black magic that Consuelo and Aura are weaving around Felipe. The use of “you” gives the reader a sense of immediacy and a false sense of agency. Aura is like a choose-your-own-adventure novel but with only one choice available — Consuelo’s.

In addition to the odd narrative voice, Aura is a bilingual novel. On the left page, you have the story in Spanish; on the right, it is in English. This split also works to draw the reader into the story even if you can’t read the other language. While reading the story in English, you can’t help but glance over at the Spanish page. It’s like it is beckoning to you, wanting to draw you into its rhythms, to pull you into its hegemony. Aside from the ways in which the dual language presentation works in the story, it’s a great way to pick up a second (or third or fourth!) language. As Fuentes once said, “Monolingualism is a disorder that is easily remedied.”

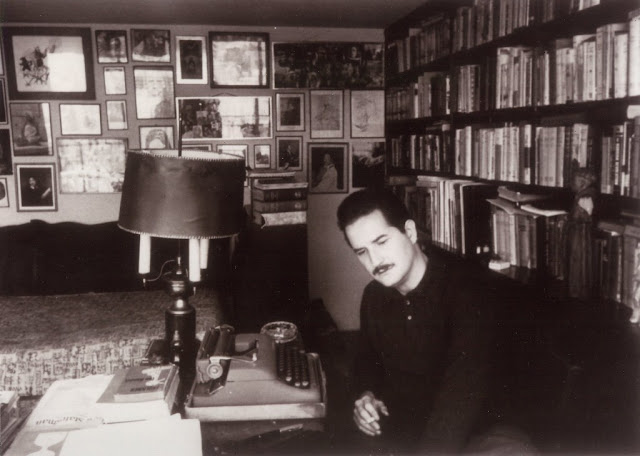

Carlos Fuentes was born in Panama City, Panama, in 1928. His father was a Mexican diplomat, so Fuentes’s family spent much of their time moving from city to city throughout Latin America. This, Fuentes claimed later, gave him an important, outsider’s perspective on Latin American culture and history.

After spending much of his childhood in Washington, D.C. (becoming fluent in English in the process), Fuentes and his family moved to Santiago, Chile, where he became interested in the work of Chilean poet Pablo Naruda. He moved to Mexico at the age of sixteen. It was the first time he’d lived in his native country. He studied law, worked for a daily newspaper, and then moved to Geneva, Switzerland, to attend the Graduate Institute of International Studies. In the late 1950s, he was the head of cultural relations at the Secretariat of Foreign Affairs. This diplomatic post only lasted until 1958, when he wrote and published his first novel, Where the Air Is Clear (La región más transparente). After this book made him a national celebrity, he was able to leave his job and write full-time.

Like Aura, many of Fuentes’s novels employ avant-garde and experimental narrative techniques. Books like The Death of Artemio Cruz (La muerte de Artemio Cruz), A Change of Skin (Cambio de piel), Terra Nostra, and The Old Gringo (Gringo viejo) bounce back and forth in time, use multiple narrators, and use cinematic techniques borrowed from Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, such as close-up, cross-cutting, deep focus, and flashback.

Fuentes died on May 12, 2012, after being found collapsed on the floor of his Mexico City home. His last message on Twitter is one that, sadly, is still prescient today:

“There must be something beyond slaughter and barbarism to support the existence of mankind and we must all help search for it.”

You finish reading today’s Blog-o-ween 2023 post. You put down your phone and pour yourself a cup of coffee. Standing in the kitchen, looking out the window, you wonder why odd thoughts leap into your mind. Thoughts that seem at one and the same time utterly alien and completely your own. You feel like you are caught between worlds, having to choose between waking nightmare and...pleasant dreams? Hmmmm? Heh-heh-heh!

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think? Let me know!