This made-for-TV movie is a good example of what I like to call a “diet giallo.”

For those of you not in the know, “giallo” is the Italian word for “yellow.” In 1929, Italian publisher, Mondadori, published a series of popular British and American mystery books translated into Italian. These books were printed with yellow covers. They proved so successful that other companies jumped on the bandwagon and published their own mystery series also using yellow covers. Soon, the Italian reading public was all about going down to the bookstore to pick up the latest “giallo.”

Giallos (or gialli if you want to be pedantic about it) soon made the leap from the page to the big screen. Mario Bava’s 1963 film La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much, a.k.a. Evil Eye) is considered by many to be the first cinematic giallo. Its mixture of thriller and horror conventions (with a little sex thrown in) would be the well that the genre would return to again and again for the next 20-30 years.

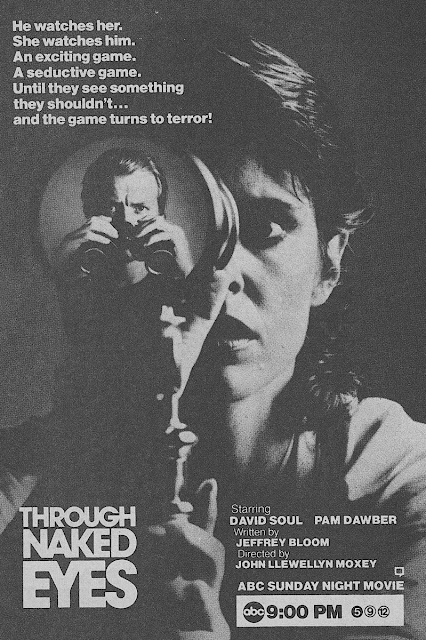

Being a “diet giallo,” Through Naked Eyes has all of the taste of regular giallo, but without the heavy calories associated with that genre’s dependency on explicit sex and blood. The plights and peccadilloes of co-stars Pam Dawber and David Soul are toned-down variants of what one would hope to find in a Dario Argento or Brian De Palma flick.

While that may sound like a set-up for a glib dismissal, I assure you it is anything but. Through Naked Eyes is a lot more interesting and kinkier than you would expect from a made-for-TV movie. It has quite a bit to say about modern, urban life, the ways that we distance ourselves from one another, and how those distances affect the way we perceive others.

Plus, there’s peeping. And a groovy synth soundtrack. And a black glove-wearing murderer. It’s pretty much got it all!

The film opens with aerial shots of Chicago. It’s the middle of the day, and a radio announcer tells us in voiceover that the city is in the midst of a horrible heatwave that will probably last the rest of the week. The mobile camera comes to rest on an apartment complex, its twin buildings connected by a large lobby. Emerging from the elevator into this lobby, an old man collapses and dies with a knife in his back.

Anne Walsh (Pam Dawber) and William Parrish (David Soul) are residents of this complex; he in the north tower, she in the south. Police, TV reporters, medics, and other residents gather below while the old man’s body is removed. William pulls out his trusty pair of binoculars and watches the proceedings. He scans the apartments in the south tower across the way. People lean from their windows to follow the action. William continues to watch the watchers when he pulls up short – there, in the apartment opposite his, a woman is at a telescope watching him!

Thus begins a very odd courtship between Anne and William. Each watching the other watch them. The movie does not disparage this arrangement, doesn’t treat it as sordid or immoral. These are two adults who willingly and knowingly engage in peeping.

Alas, the police take a dim view of William’s and Anne’s mutual voyeurism. Detectives Wylie (Dick Anthony Williams) and Scopetta (Gerald Castillo) think William is their guy. Scopetta lays out their case to police psychologist Dr. Muller (Fionnula Flanagan), but it doesn’t quite go as he, or the audience, plans:

Sgt. Scopetta: He’s unmarried. He has never been married. He doesn’t currently have a steady girlfriend. Lives alone. Makes pretty good money. His mother died when he was a teenager. Doesn’t have any brothers or sisters. His father lives in Miami. He’s in sporting goods, a middleman. It’s a lousy relationship...Dr. Muller: Anything else?Sgt. Scopetta: Yeah. William Parrish peeps.Dr. Muller: What?Sgt. Scopetta: He uses binoculars. Him and a lady friend of his, they both peep. At each other.Dr. Muller: Sounds like fun.

Surprisingly, Dr. Muller does not see mutual peeping as a problem. This is a refreshingly enlightened attitude, especially for a TV program at the time. America had taken a conservative swing to the right with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, and deviant sexualities were in the crosshairs. Dr. Muller goes on to reframe Scopetta’s case file on William, making him seem less of a homicidal maniac and more of what he really is – a lonely man:

He’s a professional man in his mid-thirties. Got a lousy relationship with his father. Maybe they even hate each other’s guts, but what else is new? He’s single – not ‘unmarried’ – single. He lives alone, he dates irregularly, devotes himself to his career, and on occasion he titillates his libido by practicing man’s most common sexual diversion: girl watching.

As the bodies pile up, however, Scopetta and Wylie still think William is their man. They try to drive a wedge between the young couple, who by this time have moved past peeping and into "going out to dinner" range of each other.

Unbeknownst to the everyone, however, Anne’s and William’s relationship is a ménage à trois. Someone, it turns out, is watching the watchers. Someone who likes taking pictures. Someone who likes wearing leather gloves. Someone with a set of steak knives that’s missing a few pieces.

Written by Jeffrey Bloom (Blood Beach, Flowers in the Attic, and episodes of Starsky and Hutch) and directed by “Mr. Made-For-TV” himself, John Llewellyn Moxey (A Taste of Evil, Smash Up on Interstate 5, and episodes of Mission: Impossible, Magnum P.I., and Murder, She Wrote), Through Naked Eyes has got a nice groove to it – and I’m not just talking about the synthtastic score written by Guy Melle!

There are red herrings aplenty: could the killer be William’s fellow symphony member, Karen (Amy Morton), who desperately wants William to come and stay with her? Or could it be Terry (Rod McCary), Anne’s writing agent with whom she’s been sharing more than just the customary 10% fee, if you catch my drift? Even Anne and William are painted as plausible suspects during the proceedings.

All of the actors are given a chance to shine. David Soul does good work making William seem like someone unaccustomed to human contact. The scene between William and his father (William Schallert) is poignant, with both men slowly and painfully revealing their emotional scars to each other. For those of you who only think “comedy” when you hear the name Pam Dawber – and, let’s face it, considering her excellent work in Mork and Mindy and My Sister, Sam, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking that – rest assured that she plays “erotic thriller heroine” just as well. Dawber’s portrayal of Anne’s sexual confidence and vulnerability is finely balanced.

Those of you who like to play the “Hey, it’s that guy!” game should be on the lookout for John Mahoney and Dennis Farina. The Internet Movie Database (IMDb) claims that Donald Moffat (“Garry” from The Thing) is “Patrolman #4,” but the name of the actor in the end credits is actually Don Moffett. Seems like a totally different guy.

Through Naked Eyes plays like a giallo, that venerable Italian cinematic genre that was a potent mixture of mystery, violence, and sex. Because it’s a made-for-TV movie, however, it can’t rely on gory set-pieces or explicit sexual content. Instead, it focuses on some of the Hitchcockian tropes that were also a part of the DNA of gialli, such as featuring a protagonist who is forced to venture where the police fear to tread in order to investigate a series of horribly violent crimes.

The most important Hitchcockian trope on display is voyeurism. Watching and being watched is at the heart of Through Naked Eyes. The harmless peeping that Anne and William engage in isn’t the only voyeurism dealt with here, however. Through Naked Eyes shows the viewer (inside and outside the movie) just how compartmentalized modern life really is.

We see life happening from afar, whether it’s through our binoculars or our TV sets, and we make judgments based on those observations. Because of the distances between us, we can’t tell what other people are really thinking or feeling, so we project emotions and motives onto them. We think we understand other people, but we really have no idea what another person is all about until we interact with them.

Everyone in Through Naked Eyes engages in some form of voyeurism and comes to a wrong conclusion because of it. Anne and William watch each other, but they don’t have a real sense of who the other person is or why they are being watched in return by them. Anne sees William and his father argue, but she doesn’t know why. She sees William get angry, but doesn’t realize that it’s because he wanted to open up to his father, but didn’t take the chance. Her fears that Sgt. Scopetta may be right about William color her perceptions.

Sgt. Scopetta, too, is engaged in voyeurism. He watches William from afar and assumes that he is a pervert and, therefore, the murderer. Dr. Muller takes Scopetta’s views of William and builds an entirely different person from them.

The viewer, too, is a voyeur. (You aren’t getting off that easy!) We see the characters and make snap judgments about who is guilty or not based on what we see or our experiences with the genre.

In a review that I found on-line, it was pointed out that since the word “Naked” was in the title there should have been some nudity. The reviewer was perhaps being a tad facetious, but I think it’s an important point. Why is it called Through Naked Eyes, after all?

I may be stuffed full of wild blueberry muffins, but I think the use of the word “Naked” in the title is a cry for us to set aside our telescopes, binoculars, and cameras. To see with “naked” eyes means that we don’t need the eye of the camera to see. We’ve closed the distance to other people and can better see their lives as they really are. It’s the first step on the road to understanding.

Of course, that may just the mad musings of a Film Studies major. Through Naked Eyes is currently on Amazon Prime and YouTube. Peep on it for yourself and let me know what you think. I'll be watching...

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think? Let me know!